The Whole of the Moon

Eulogy for Mark Christopher Rowson: 1975-2021

Aberdeen Crematorium, November 11, 2021.

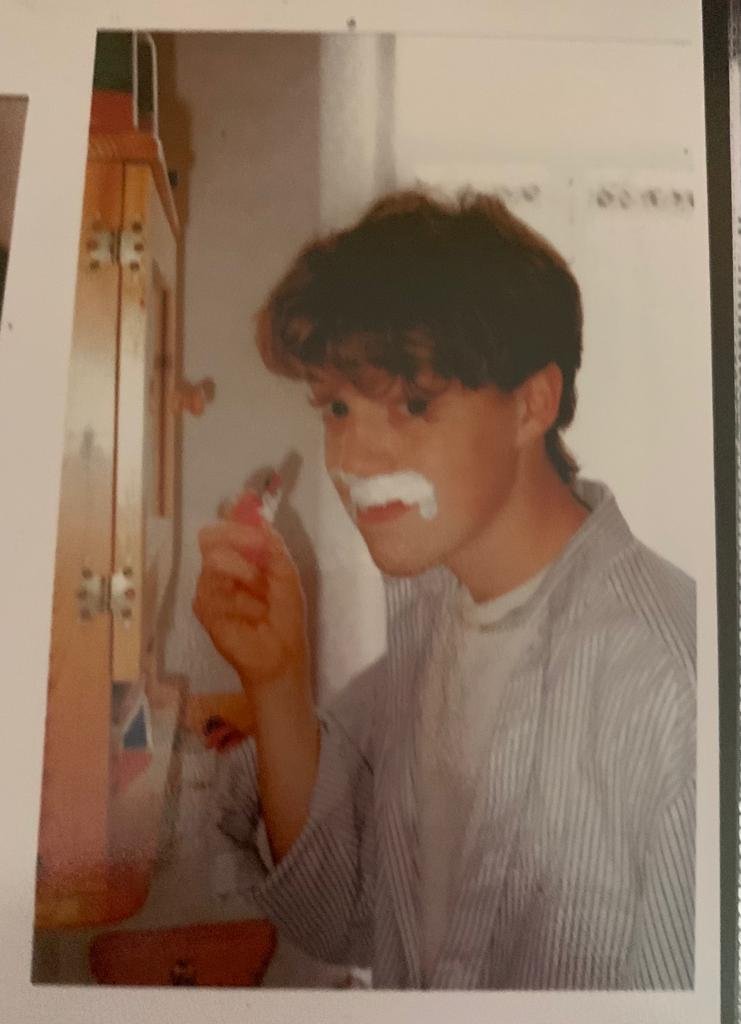

Mark when he was sixteen.

Thank you John for being our celebrant today, and thank you to everyone in the room, and those watching from afar; I know you wanted to be here, and you are.

Like Mark, I enjoy speaking, but this is my first eulogy, and Mark was my only brother, so I’ve been advised not to look any of you in the eye, in case our shared sense of loss leads my lips to wobble. Yet the tremor in our souls that makes our lips wobble is distinctively human, and surely the best of us. Those feelings are what we are here to stay in touch with, so I’m going to trust them to do their thing.

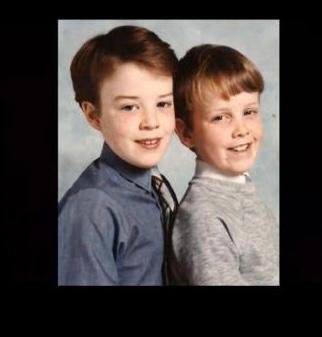

Together at Skene Square primary school.

One of the hardest things today is that grieving for Mark began a long time ago. Many of you knew Mark as a precocious child and radiant young man. Some of you only knew him as he the vulnerable adult in social care that he later became. But Mark’s life can be viewed as a whole, and that’s what I seek to convey and celebrate, inspired by a song Mark loved that we’ll hear shortly: The Whole of the Moon, by The Waterboys.

Mark was just over two years older than me. In my formative years, he knew a little more, ran a little faster, climbed a little higher. I looked up to him literally and figuratively. He was the smart one, actually. He was also the chess player I had to become good enough to beat. I created some momentum for myself in the process and kept getting better in a way that defined my life; without Mark, none of that would have happened. All lives have these kinds of consequences.

That relationship between two boys in their tender years stayed between us as memory and bond even when our lives went in different directions. The connection was not easy to maintain over the years, but I felt it when we were together at Christmas time. We would ritualistically go outside and smoke an annual cigar. I don’t smoke, but loved doing something simply to be together, like we used to.

Over the last few days, I have been looking at photos of Mark in his first nineteen years of life. There we see him as most of us might choose to remember him: youthful, handsome, intellectual, creative. Mark the force of nature we have been blessed to know; a radiant and playful fellow with abundant charisma and charm.

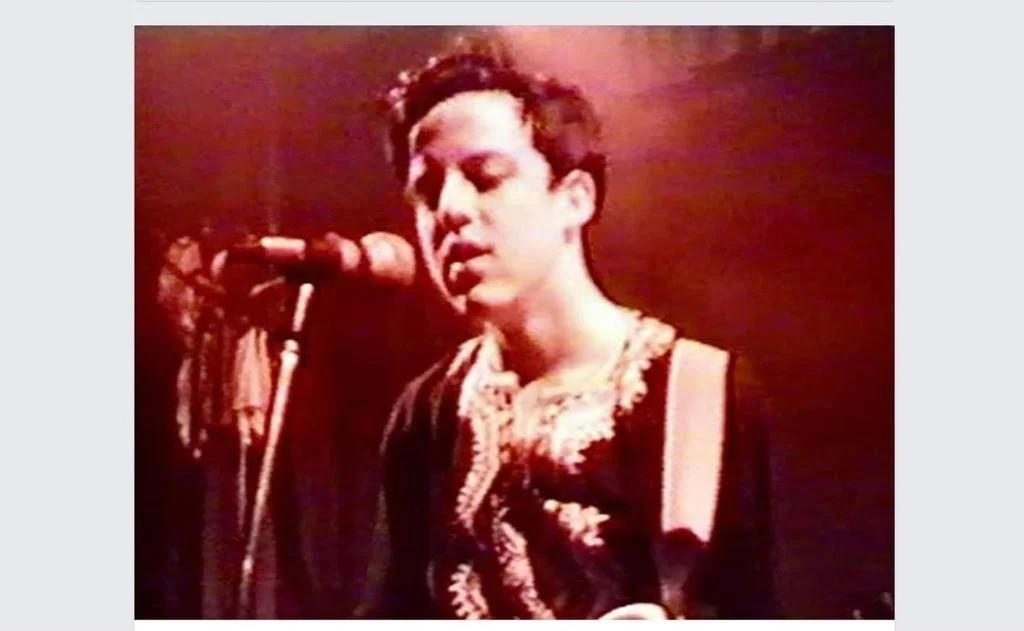

Mark was the rock star for whom the dream never died.

Mark at the Aberdeen Grammar School concert c1993

Mark was the cricket player who cried 'Howzat?!!' in his sleep.

Mark was the poet and the songwriter who dyed his hair blonde and wore pink shirts to school as a gentle act of rebellion.

Mark learned O-level Russian just for the hell of it, and he walked around town with the complete works of Oscar Wilde in his bag.

Mark loved food and made massive three-tier sandwiches with fresh doorsteps of wholemeal bread, margarine, salad, Branston pickle, and cheese (before he was Vegan).

Mark had moments of sensitivity too. In 1987 he made a wooden grave for our beloved Siamese cat, Thai, in the back garden of 53 View Terrace with his own poem and drawing, and he planted a Clematis plant there that still carries blossom into the back lane to this day. Again, our lives have a way of leaving their traces.

This Mark was also flamboyant and carefree, He blew his first student loan payment, meant for three months on a lavish trip to Edinburgh with a friend – taxis, restaurants, shopping, hotels - over a mere three days. But he came home overflowing with vitality and clearly didn’t regret a second.

That Mark is easy to love. Mark had a bright future on the cusp of adulthood. He was full of potential and possibility. That Mark inspired us and made us feel alive. Our memories of that Mark are the joy of his life.

But that is not the meaning of his life. For the story does not end there.

It would be a disservice to Mark’s memory to imagine that what happened next should be swept under the rug as the mere dust of time. What happened next was most of Mark’s existence, it lasted over a quarter of a century, and it has its own kind of mattering.

The truth is Mark was profoundly unlucky. We don't quite know how it happened, and we can’t make sense of why, but in his late teenage years some combination of genes, substances, and circumstances changed the course of his life, almost certainly for the worse. The condition is called schizophrenia. Some doubt it’s a single condition at all because it manifests in so many ways, but the patterns of distorted thought that the term signifies happen to about 20 million people worldwide. Mark just happened to be one of them. Schizophrenia is a socially debilitating condition that tends to isolate you over time. The condition also tends to gradually wear down the body, which is what happened to Mark, who spent over about 28 years in some kind of hospital or supported accommodation as mental illness became physical, as it invariably does.

I vividly remember a liminal moment between the two Marks, when we were not quite sure what was happening to him. Mark was eighteen, outgoing, radiant in intensity, on fire with his social life, and keen to share one of his many latest ideas. One night at the kitchen table in Cornhill Road, which many of you will remember, Mark proclaimed that each of his fingers had a colour, and asked me to guess which was which. I played along cautiously and my first guess was right, but part of me already knew something had tilted. This was not eccentricity. This was insanity. And it would get much worse.

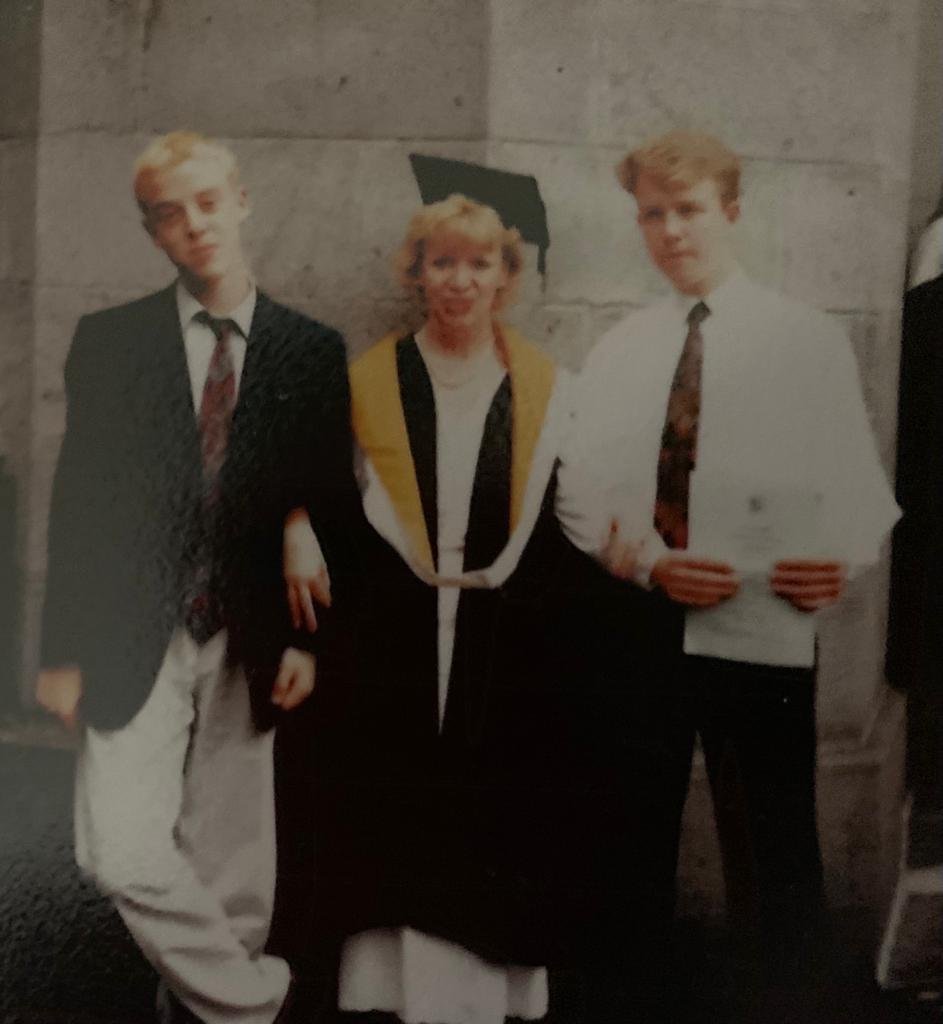

At our mum’s M.Ed Graduation c1997.

There were bleak moments in those years of psychiatric and community care and it feels right to remember some of them too. The aim is not to dwell on them, but nor do I want to suppress them. I want to release the atmosphere they evoke, to release Mark in our memory, and help him rest in peace in our minds.

And so I remember the graffiti he penned on his walls - the boundary of his world that his imagination always reached beyond.

And I remember the word ‘Sectioned’ and all that it means, not least the time we escaped from the hospital together and Mark leaped in the air, saying “I’m free, I’m free”. Then a police car was called to bring him back to his ward and his compulsory medication, and not because he had committed any crime.

And I remember the clothes that got bigger, the extra extra extra extra large clothes that I didn’t even know existed, but which he needed due to the impacts of his condition and medication.

And I remember, near the end, when his lungs began to give way, and the lack of oxygen led him to drift in and out of consciousness, he would still smoke, and cigarettes would sometimes burn into blisters in his hands as he fell asleep.

He was never the easiest patient, mostly because he didn't think of himself as a patient at all.

He remained a gentle rebel to the end.

It was tragic. It really was.

But then life is.

And yet it is so much more too.

There is no blame for what happened. And no shame in it either.

As we heard in the lyrics coming into the service today: love is not a victory march. Sometimes, it’s a cold and it’s a broken hallelujah.

Mark’s life can be thought of as a broken hallelujah. Schizophrenia happened to him before a career or family helped his identity to mature into an evolving pattern. His life was characterised by suspended animation and arrested development, in which the personality, utterly charming though it was, could not grow or blossom as we would have hoped.

The joy of Mark’s life endures in our memory of his youthful vitality, charisma, and charm. But I believe the meaning of his life is more subtle.

To put it politically - and Mark would have - we are not fascists. He was debilitated, and almost three decades of care that Mark received shows what it means to live in a civilised society. That’s a fragile achievement that I would like Mark’s life to help us remember.

His life revealed the loyalty of friends and family too, especially the tenacity of a mother’s love. Mum never gave up on him. Never hid him away. Never stopped trying to bring him back to the life we had hoped for him to have. And this was gruelling work, mostly in vain, and only bearable because of the steadfast support of her husband Ray. And my father, with many mental challenges of his own, never stopped being Mark’s dad. He did what he could, offering pocket money, visiting regularly, and in the time-honoured tradition of parenting, giving advice that was mostly ignored.

Out for lunch in Stonehaven with mum, around 2015.

We thank extended family too – particularly Hazel and Bob for feeding Mark food he particularly loved – Mark called them “kitchen spectaculars”. Hazel was the last person to be with him before he died; when apparently he asked after almost everyone he knew – his mind was full of memory, full of people he held in high esteem.

I also thank his long-time community psychiatric nurse Kenny Keating and his most recent Social Worker Rachel Smith; they made their own personal contributions but represent many others. Also, Corgarff Ward in Cornhill Hospital took great care of Mark during Lockdown, when his general health significantly improved. In January of this year, Mark moved into Westerton Crescent which provides Supported Living Accommodation for adults with complex needs - he talked of it as home, in a way that carried conviction. He was well-loved and looked after until the end.

The joy and the meaning of Mark’s life co-arise. Although Mark remained an adolescent, that was not altogether bad because he had a profoundly happy adolescence. His soul remained suffused with gladness at being Mark and at being alive. His inner life was more interesting than it is for many, and in general I believe he was not any less happy than most of us. Let us remember that, and also his great undulating belly laughs.

There's a part of me that wonders if there was ever a way back for Mark after the initial psychosis took hold. My mum and I have often discussed it. I suspect there was, but it was probably a narrow path, and not easy to find or walk in this kind of society with the view of the mind it has. And let us not lament the life that was actually lived. For it is no truism to say each life is precious. Mark meant more than his glory days. His unique place in the tapestry of life is his deeper darker glory.

I’m coming into land…

Mark wrote a lot of song lyrics. I remember one that Mark sang to me about ten years ago. The line goes: “Didn’t you realise when you were young, the sun —has to go —-down.”

Death will come for all of us.

Life is richer for knowing that.

In a few moments, you’ll see many delightful photos of Mark, mostly in his first twenty years, and we’ll all have our favourites. I was most struck however by a bittersweet image near the end in which Mark is in hospital, his health is clearly compromised, but he is looking at the camera with his thumbs up. The confident adolescent lives on in the compromised adult body, and it lives on still. (The image is too personal to share on this page).

Mark stayed in many houses, many rooms, many apartments, and many wards, but he rarely seemed to be in exile. His self-belief was such that wherever he was, even if just behind a curtain, he brought his guitar and his magazines and his snacks and found his own kind of sovereignty and dignity. My mum and I once joked that despite everything Mark went through, and however his life appeared to the outside world, he always saw himself as the king of the castle.

I put this idea to one of Mark’s long-standing friends, Nicky Smithers - that Mark always saw himself as the king of the castle - and he added:

“The thing is, he was.”